GARY LOCKWOOD DOESN’T believe in motivation. He didn’t get the body he has today (lean, gristly, a bit scary) simply by being motivated. He didn’t become the CEO of 24/7 Fitness because he wanted it enough. And he says as much to his clients. ‘It doesn’t matter how much motivation you have,’ he declares, pronouncing the word as if it were a nasty kind of intestinal worm. ‘There is no substitute for just fucking doing it.’

As for willpower – usually defined as the ability to resist short-term rewards in pursuit of longer-term goals – Lockwood is similarly dismissive. ‘You will not get what you want in fitness or life relying on willpower.’ Willpower is fragile. You might win the battle with your will one day, then lose it the next. The key to ‘just fucking doing it’ is what he terms discipline. ‘Discipline kicks your butt out of bed on cold winter mornings and drags you to the gym for an hour of mind-numbing cardio.’

Some people think there’s some magic pill they can take, he says, or some mystical hack to do with carbs. ‘The truth is, you have to be disciplined. The harder it is, the more discipline you need. How much you want it? It’s irrelevant.’

The dopamine trap

In the past 10 or 12 years – the Instagrammian Epoch, if you will – we’ve happily embraced the idea that the people who are rich, thin, toned, successful and happy must have incredible amounts of motivation. They have the power to resist Krispy Kremes, Instagram Reels, Five Guys fries, the Devil himself. By implication, those of us whose lives are a little flabbier, carbier, sloppier, sinnier, must be lacking in these virtues.

But whether or not you buy into Lockwood’s approach – inspired by the neo-Stoic philosopher Joe Rogan, incidentally – it’s hard to disagree with his central thesis: that mere desire to change is in itself insufficient for change. Moreover, he’s far from the only person who has come to view the word ‘willpower’ with suspicion. (Whether ‘discipline’ is really so different is another matter.)

‘Those of us who don’t overeat aren’t white-knuckling it. Our urges simply aren’t that strong’

‘I’m not sure willpower is the best name any more,’ says Pete Williams, a scientist at the Institute for Functional Medicine, who takes a gentler approach with his clients. The main problem for him is that willpower comes with a lot of baggage. It implies a moral failing that only increases the stress and shame associated with being overweight. Which helps no one to actually lose weight.

‘A lot of patients have a very negative relationship with themselves because they believe they don’t have willpower,’ he says. ‘Most patients who come to us generally understand what they need to do to get better.’ The problem is that much of our unhealthier behaviours are driven by the unconscious. ‘They don’t know why they do it. They just can’t help going to the fridge.’

Williams has devoted much of his professional life to understanding why this should be. Some people are irresistibly drawn to high-calorie foods; others can happily sit next to a plate of biscuits and not take a bite. Some skip cheerfully to the gym in the mornings; others find it difficult just to drag themselves out of bed. ‘The question we’ve asked is: is there any genetic basis to that variation?’ says Williams. ‘And the answer to that is yes.’

Williams’ research focuses specifically on dopamine, which plays the central role in our brain’s reward centres. Dopamine acts as both a hormone (it’s a close relative of adrenaline) and a neurotransmitter, which means it sends messages down pathways in our brain that govern different behaviours. One of those pathways, the mesolimbic pathway, has strong associations with reward and anticipation, and thus habit formation, motivation and addiction.

‘What the literature shows us is that if we have a patient that has gene variations around dopamine, they are more likely to show adverse behaviours,’ says Williams. ‘The patients with lower dopamine are always looking for how they can fill that gap, often through harmful behaviours: sex, drugs, rock ’n’ roll, binge-eating, shopping, gambling. They’re always seeking the daily reward because they never quite get enough dopamine.’ He’s found that this is a common trait in business executives who never feel satisfied with their achievements, no matter what they do. ‘It’s not that they haven’t got any willpower.’

Another key insight is that the higher your levels of stress, the lower the availability of dopamine and the higher the likelihood that an individual will fall back on compulsive activity: doomscrolling, shopping, vaping, drinking, binge-eating. ‘Everything falls apart when you have an individual who is under a higher-than-normal stress load for longer than expected, and without the resources to be able to deal with it.’

That’s rather a bleak message, I say. We’re prisoners of our genes and our circumstances? But Williams insists that the opposite is true. ‘We’ve had plenty of clinically obese patients who have very negative self-esteem not only about the way they look, but around the fact that they don’t have any willpower. And it’s been completely enlightening for them when we say, “Look, this is a part of you that is unconsciously controlled.” They learn that there are forces that are genetically led that are driving [them] to make those decisions. We get positive outcomes very quickly by changing the narrative for that patient.’

Stop signals

Given our society’s conflicting notions of want and reward – the Christian importance of resisting temptation overlaid the capitalist importance of advertising – it’s not entirely surprising that we’ve made such a false god of willpower. In his 2012 book on the subject, American social psychologist Roy Baumeister termed it as ‘the greatest human strength’, defining willpower as ‘the energy that people use for self-control and making decisions’.

The most famous test of willpower – perhaps the most famous psychological experiment of all time – is ‘the marshmallow test’, devised by Walter Mischel at Stanford University to measure the self-control of five-year-olds. It’s fun to try it on any small children in your own life. Place a pile of marshmallows in front of them and tell them that they’re allowed to eat one marshmallow now – but if they wait 15 minutes, they’re allowed two. In the decades following the study, Mischel discovered that the children who held out for double marshmallows were more academically successful, richer and less likely to take drugs or commit crimes. The experiment reinforced the idea that success depends on mastering self-control. Baumeister positioned willpower as a ‘superpower’ that withers and weakens when you fail to use it, like a muscle, and depletes when you’re tired or hungry or stressed.

Recently, however, this thesis has taken a bit of a kicking. ‘Willpower is overrated’ was the conclusion of a 2021 study, which found that willpower is not only ‘fragile and not to be relied on’, but also that the most successful people rely less on their willpower than others.

Moreover, the marshmallow test has proved stubbornly hard to replicate in subsequent experiments. Self-control is dependent on a whole range of deep factors (social status, upbringing, income, etc) as well as more acute pressures of stress, exhaustion and hunger – to say nothing of genetic variations. Children from rich families are better marshmallow-resisters than kids from poorer families. But that’s not a lack of self-control. It makes sense to eat now if you don’t know where your next meal is coming from. It’s also sensible to be suspicious of men in lab coats promising marshmallows.

‘Some people do find it more difficult to say no to food. But you don’t find it more difficult because of some internal moral failing or lack of will’

Then there’s the view that we’re less in control of our own destinies than most of us imagine. ‘We tend to place far too much emphasis on our own executive capacity to direct our own actions,’ says Giles Yeo, professor of genetics at Cambridge University. In reality, we’re all largely at the mercy of our genes and environment. ‘Some people do find it more difficult to say no to food. But you don’t find it more difficult because of some internal moral failing or lack of will. You find it difficult because of underlying causes in the biological system.’

When it comes to overeating, it helps to understand how appetite works. Dr Yeo conceptualises appetite as a triangle. There are three sides to it: hunger, fullness and reward, all governed by different parts of the brain. If you’re full, you cease to be hungry – at least until someone offers you an extremely rewarding item of food, such as chocolate or cheese. If you’re extremely hungry, the most basic item of food will taste delicious to you. If you pull on one corner, you change the overall shape of the triangle.

Dr Yeo stresses that this happens in the brain, not the belly. ‘All of the 1,000-plus genes that we have identified that influence your body weight act within the brain, and all of them act on the appetite triangle,’ he says. ‘Some of the genes make you feel hungrier. Other genes make you feel less full for the same amount of food. Other genes tackle the reward element, which means you either need more or less food or different types of food to give you that same rewarding feeling.’ Each of us will experience hunger and fullness differently.

This is where Ozempic, Wegovy and the new class of obesity drugs known as semaglutides come in. ‘They’re not really weight-loss drugs at all,’ wrote Albert Fox Cain in an article for Business Insider. ‘They’re something far more powerful and surreal: injectable willpower.’ What semaglutides actually do, explains Dr Yeo, is ‘smack the fullness side of the appetite triangle really hard’. Generally, those of us who don’t habitually overeat aren’t spending our lives white-knuckling it – our urges simply aren’t that strong.

Still, semaglutides remain rather blunt instruments – and their effects on our reward pathways are still not fully understood. Moreover, our genes are only part of the story. Humans have always had this spectrum of genetic dispositions… but we haven’t always been obese. ‘What has changed is the environment,’ says Dr Yeo. ‘I’m a geneticist, but I end up talking about the environment all the time because your genes interact with the environment. The environment has revealed our genetic susceptibility to obesity.’

Matter over mind

In his recent bestseller, Ultra-Processed People, the doctor, author and presenter Chris van Tulleken argues forcefully it’s a change in the food environment – namely the invention and mass-marketing of cheap, addictive, ultra-processed foods – that’s really what’s behind the rise of obesity over the past 50 years, not some mass societal collapse of self-control.

‘Whenever anyone tries to study “willpower” it turns out to be very hard to nail down,’ Dr van Tulleken explains. ‘I would define it as a collision between motivation and opportunity, in other words nearly purely about your environment and nothing to do with your character.’

For most people, the availability of foods that support healthy weight loss is low. ‘They can’t afford it and it’s not marketed to them,’ he says. ‘So even when motivation is extremely high, weight loss is nearly impossible for the most affected people. “Low willpower” turns out to be a proxy for “poverty”.’ Fast food outlets and billboard ads tend to proliferate in poorer areas. Some poor people will have the genetic advantages to survive this. Many will not.

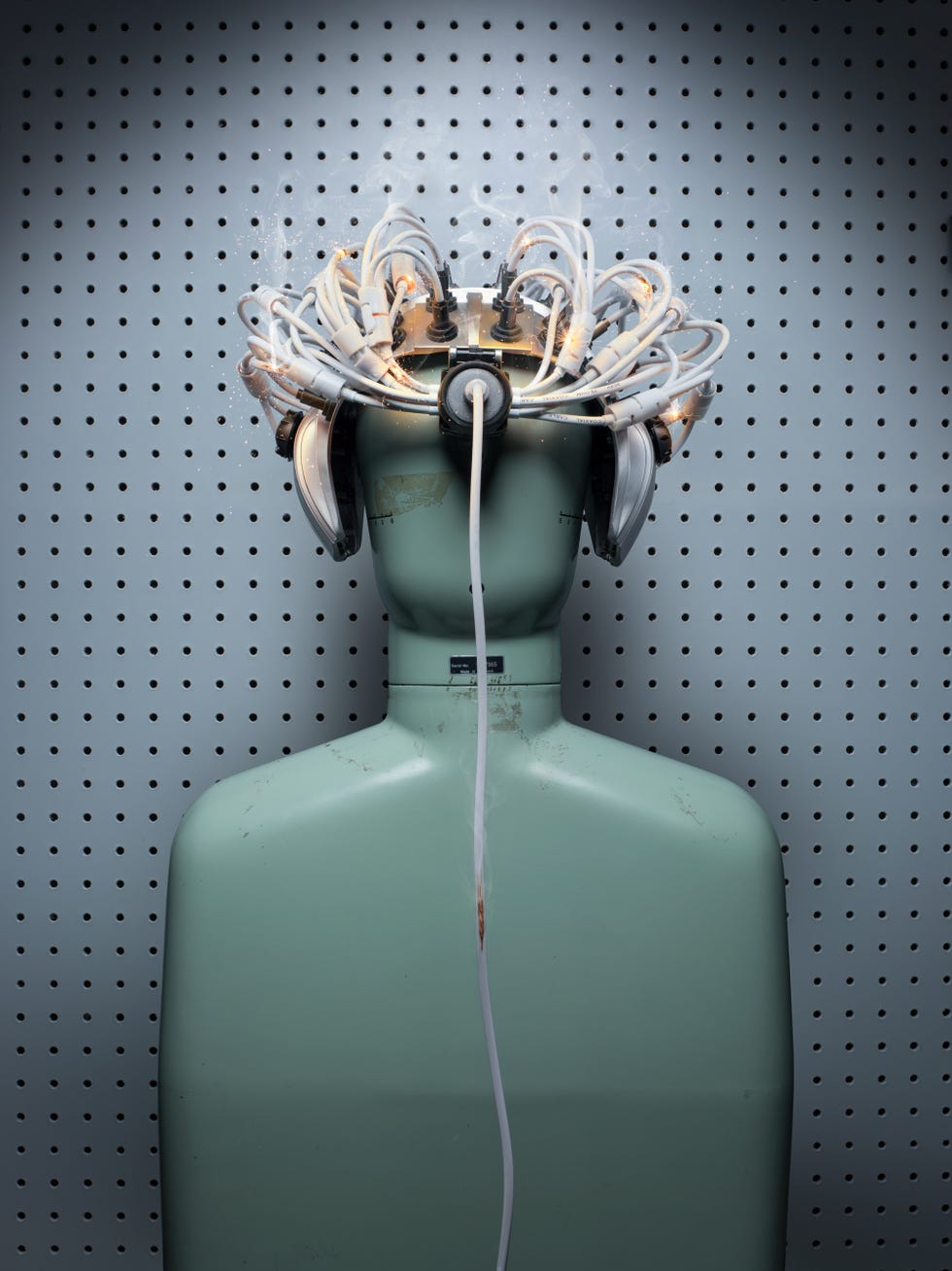

Of course, it’s not just food companies that are jangling our reward centres at every available opportunity. I first started hearing the term ‘dopamine’ in the tech world circa 2015. In her recent book, Dopamine Nation, Anna Lembke, a leading addiction expert based at Stanford University compared the smartphone to a ‘hypodermic needle’ and argued internet pornography, gambling sites, TikTok, clickbait, the lot of it, is all engineered to create habits and addictions. The critic Ted Gioia recently coined the term ‘dopamine culture’ to decry a wider turn away from enlightenment and entertainment to addiction. Think of the way Netflix is constantly feeding you more shows or Instagram pumps out more Reels. It’s where the money is.

Williams studies dopamine for a living and he’s in no doubt that a great deal of companies are doing this quite deliberately. ‘With most of these problems – gambling, compulsive shopping, drug addiction – the underlying mechanisms and pathways that drive them are very similar, if not the same. I would be very surprised if these companies don’t have good scientists who understand catecholamine pathways, the neurobiology of addiction, and so on.’

‘The more decisions you have to make – the more you rely on your willpower – the more that you’re setting yourself up to fail’

Dr Yeo stresses that the surest way to change behaviour is to change your environment. A large part of that is political: both Dr Yeo and Dr van Tulleken are in favour of much tighter regulations on food companies. However, as Dr Yeo says, ‘The environment you can control tends to be your household.’ If you buy a packet of Cadbury’s Chocolate Fingers you have to make 22 decisions not to eat each one. If you don’t purchase the packet in the first place, that’s one decision. The more decisions you have to make – the more you rely on your so-called willpower – the more that you’re setting yourself up to fail.

This may still leave you with the feeling that change is essentially impossible. Ben Bidwell, a human potential coach with the app Arvra, believes we can change – just as long as you don’t rely on willpower alone. He subscribes to the idea of willpower as a muscle: ‘It gets tired.’

What you can do, however, is to tell a better story about yourself, a more honest story, one that takes account of the person you are but also the person you might become. ‘Look at the kind of person you want to be,’ he says. ‘What kind of behaviours does a healthy man possess? Does he drink alcohol three times a week? Does he walk up the stairs or use the lift? Does he have a cupboard full of sweets? Does he buy fresh natural foods?’

He then attempts to lock-in that fresh identity by means of ‘easy wins’. His advice is to start small. ‘Let’s say your intention is to read 20 pages a day and you’re not doing it. Just set the intention to read one page a day. You will definitely do that. And once you’ve done one, it doesn’t seem so hard reading a bit more. It’s the same with the gym. Tell yourself you’re going to do some squats and anything else is a bonus. That’s not so hard. And once you do the squats you’re in a different mindset and the other stuff is way easier.’

He also advises controlling your environment to take account of your weak-willed future self. ‘Leave your gym clothes out when you go to sleep so they’re really easy for you to put on when you wake up. Have your protein shake in the fridge ready-made. Remove as many of the obstacles to getting to the gym as you can. Otherwise, you’re just relying on willpower and it’s going to run out.’

Bidwell’s gently-gently approach – influenced by the doctrine of James Clear, author of the bestseller Atomic Habits – at first seems opposed to the Just Fucking Do It attitude expounded by Gary Lockwood. But he feels that the two approaches are more interlinked than they first appear.

‘We have this old phrase, mind over matter. And for me, it’s really, matter over mind. We’re fighting this battle with our minds. Our minds are constantly saying, “No! No gym!” But place your body in the gym and the mind softens. We do the matter, then the mind is like, “Oh, okay, I did do that. And it was okay.” Eventually, the mind is like, “I can’t tell you not to do this because every time it was okay! Let’s just go do it.”’

If what it takes for one person to lose weight is military discipline and for another it’s gentle hacks, doesn’t that just reflect the spectrum of human variability? That’s certainly Dr Yeo’s conclusion. ‘I think where we’ve broadly gone wrong is to think that there is a one-size-fits-all approach to weight. We need to embrace the point that actually there are going to be some people who respond very well to something like Weight Watchers, there are going to be some people who respond to keto – or whatever. Not everyone will.’ There will be something out there that works for you, he says. ‘And that’s what we need to embrace.’

This article originally appeared on Men’s Health UK.

Related:

Fatal Distraction: The Threat Addictive Technology Poses To Your Health And Wellbeing