1.

On the morning of April 14, 2020, Nedd Brockmann awoke with a desire to simply run – and run far.

The sky was still bruised with twilight when he stood in the driveway of the cattle farm his family owned west of Forbes, dressed in baggy footy shorts and a rugby training top; a uniform from those days spent out on the field with eyes alert, elbows tucked, and a shoulder always angled so as to inflict maximum damage upon impact. The top hung looser now. Mileage may have stripped Nedd of any excess body fat, but it did little to diminish his appetite for voluntary suffering.

At 5:30 a.m, he hit the road. The stiffness of sleep fell away quickly and a cautious stagger gave way to long strides. Even in the eerie stillness of daybreak, he could feel the heat of the Australian sun baked into the tarmac. It licked at his heels with each step, but this he had expected. Everything else – the distance, the pace, the monotonous turnover of legs that weighed heavy with fatigue – was left uncertain. Previously, the furthest he’d ever run was a marathon distance of 42.2km. Adding another 18 kilometres presents a sizeable question mark that hovers over the shoulder like a bad wingman at a party; most want only to distance themselves from such feats, to turn away and find better company. But the local Woolworths was 60 kilometres from the family farm and Nedd had set out with only this destination in mind. That’s the thing you come to learn about a guy like Nedd Brockmann: no matter the struggle, he likes to finish what he started.

As Nedd’s silhouette loped along that never-ending stretch of Bedgerabong road, life slowly took shape around him. Curtains were drawn open, light filtered into warm rooms, the kettle whistled its song. People in Forbes pulled themselves up into the morning and pressed start on their daily routines, oblivious to the man outside who was projectile-sweating through a rugby top that did little to prevent chafing. As Nedd approached the halfway mark at Jemalong, he spotted his mum’s car up ahead and a hand waving a bottle of water and a packet of Sour Patch Kids out the window. It’s not exactly what the mind conjures when it thinks of optimum nutrition for feats of endurance, but when you’ve run 32 kilometres on the fumes of determination and grit alone, what’s a further 28km with a throat dry and constricted from a sudden assault of citric acid and corn syrup?

He’d told his mum he wanted to get to Woolies in under five hours. When Nedd hit stop on his watch at the 60km mark, the time read four hours and fifty-six minutes. The battered sneakers he’d found in his closet a year prior offered about as much cushioning as a sheet of cardboard. He couldn’t lower his arms down next to his armpits without feeling the acute pain of skin rubbed raw. Lack of nutrition had depleted his body of all energy. And yet, despite the agony of muscles betrayed by sheer willpower, he felt euphoric. At 21-years-old, Nedd had landed on a high unlike any other and unlocked an impulse that lay deep within.

It would have been easy to chalk it up to nothing more than the invincibility that befalls those drunk on dehydration, but back at the farm, outstretched on his bed, Nedd began to wonder just what his body was capable of. That first 60 kilometre run seemed only to confirm what he already knew: that his would be a life spent in competition against himself and those unseen forces that threaten to derail us from our dreams. And when you’re a man that likes to finish what you started, such a road grows impossibly more steep.

2.

Had you met Nedd during his school years, maybe you would have sensed that he was destined for greatness. You would have felt the stirrings that overcome those in his company – a perceptible uplift in attitude, a sudden positive disposition, a desire to take on the insurmountable, if only to feel most alive in those moments of struggle – and you would have known: he is one of one. But maybe it’s also true that you would have missed all of this and, like the school coaches consumed by the hyper-competitive nature of sport and need for instant success, failed to see the combination of potential and discipline housed within this individual. Maybe you would have then disregarded the young lad who made up in mental toughness what he lacked in physical talent.

Separated from family and familiar surroundings at a boarding school in Orange, Nedd found solace in the regimented routine of oarsmen. In a dorm where sleeping in was the modus operandi, Nedd awoke to an alarm set for 4:30 a.m. By 5 a.m he was at the bus, ready for training that would last until the toll of the school bell. At the age of fifteen, he was already doing twelve to thirteen sessions a week with the crew. But in a sport that demands dedication and commitment from its athletes, motivation was quick to desert those relegated to the sidelines. When the first quad came to be filled with rowers fitter, stronger and more practiced at competition, Nedd watched as his fellow teammates gave up on their sporting pursuits.

It was remarkable then, that he continued to show up to training with the steely-eyed determination of someone on the cusp of making it into the crew, even though he never housed such delusions. “I just wasn’t the best. I wasn’t the most talented,” Nedd says of his rowing days, flashing a conspiratorial smile. “But I was really driven to have a crack and nail whatever I could to give it a hundred per cent every time.”

Nedd got into running as a means of healthy competition between a mate. After sustaining a shoulder injury on the rugby field, he longed for a physical outlet in which he could test himself. When a friend shared a screenshot of his Strava stats from a recent 12km run, Nedd felt compelled to get moving, if only to outrun the guy and provide a gentle ribbing in the group text exchange. At first it was just a 15km run, then a 21km. But like a banned substance, the physical and mental benefits of running seemed to infiltrate Nedd’s bloodstream and all he could focus on was a drive to push harder and run further. As Nedd himself put it: “I just went nuts with it.”

Social media likes to present a snapshot image of success within a finely curated highlight reel, yet Nedd’s post following his 60km run did little to mark the occasion as anything but ordinary. An orange thread snaked across a flat background of green with Strava’s report of distance and average pace serving as a footnote to the journey. With a swipe of the thumb, there stood Nedd – footy shorts crusted with salt stains, armpits and chest rubbed raw – outside Woolies, holding a bottle of milk like a prized medal. With his trademark humour, he captioned the post: “Me: ‘Mum we’re out of milk’. Mum: ‘Go run and get some’.

Me: ‘Mum we live 60km from Woolies and it shuts in 5 hours.’

Mum: ‘Better run fast then.’ Me: …”

The likes flooded in. Like a slot machine, his phone lit-up with notifications of comments from friends, family and the odd runner who had Insta-stalked their way onto his page, baffled by this run that seemed to come out of nowhere. The general tone was a sense of disbelief. Who even is this guy? Is he training for something? Why run that far just for the hell of it? Nedd’s run became the stuff of lore, punctuating conversations both on the running track and in the local pub. What seemed lost in the conversation though, was the fact that this is a man who still possessed that combination of potential and discipline that was otherwise overlooked on the sporting field. He may never have made first crew, but the gruelling training sessions he attended anyway served only to sharpen his resolve. And if you’d been wise enough to consider his upbringing, you would have understood that at the Brockmann family farm, lessons were instilled in Nedd so deep, they would remain front and centre of his psyche during each run.

It’s something Nedd acknowledges now, with the benefit of hindsight and maturity. But when growing up, he recognised his father’s tireless work ethic as a character trait; never to be made a fuss about, never the cause for any celebration. Theirs was a family doctrine of one foot in front of the other. “I saw a lot of drought and floods and shit like that, but I never really understood the depth of what was going on. I was always a bit too young or away at school. But Dad would go and there were days where he’d have to get up every single day from four o’clock onwards to go feed the cattle that have no feed out the back,” Nedd reflects.

“There was always this discipline he had, and never complained about it. It was always just, ‘Do the job: you’ve gotta do what you’ve gotta do.’ And the same with mum.”

Having been shown resilience from his parents by way of their work on the land, quitting was never something to be entertained, but Nedd came to be introduced to it all the same at school. “When I saw people give in, I was like, what the fuck? You don’t do that, it’s not a thing,” he says.

If you ask Nedd what it is that’s made him the runner he is today – someone with a penchant for extraordinary distances that strike fear in those who hear the total – he’ll speak less about his rigorous strength training and consistent mileage, and more about his family and that year he spent working on the farm with his dad after graduating high school. We might be a culture that celebrates the overnight success story, but Nedd’s is one of patience. It’s what he learned from his dad; that patience is sacred and demands nurturing. “Sitting back and having that year with my dad, I learnt a lot of patience. It was like, holy crap. This bloke has done this since he was 15, 16,” says Nedd.

When speaking about his family, there’s a perceptible tenderness in his voice. It’s a testament to the sacrifices he now understands so clearly; sacrifices his parents made on the behalf of their kids, all so they could have an upbringing that would grant them freedom to steer their own course in life, even if such freedom took them away from the farm. “I guess, without knowing, we were being shown discipline and being shown how to get back up and be resilient and actually not give in when shits gets hard. And that weighs on you. It makes you go, holy shit. And it was all for us kids, it was all just to get us through and make money to make sure we could have a good upbringing so we don’t have to be farmers,” he says.

Nedd pauses then, and the larrikin spirit that so often carries him through conversation turns laconic and sincere. “It was all so we can go and do what we want.”

3.

Here’s what Nedd wanted to do: run 50 marathons in 50 days. He knew that such an endeavour would cause a stir, that people would talk about it. And so Nedd wanted to ensure that he was never the centre of such attention. He wanted to bring a greater purpose to these runs and affect change in the process.

When Nedd relocated to Sydney to take up a trade, his morning commute to TAFE Ultimo took him down Eddy Avenue. He’d pass the 7-Eleven with its arctic aircon and the taxi rank that provided the bustling city with a near-constant soundtrack of the aggressive slap of a car horn. Nedd often ran the distance to his classes, but lately he’d been slowing to a walk, confronted by the homeless who crowded along the sidewalk and took refuge in the warm pockets of Central Station, where the heat from nearby coffee vendors granted temporary relief from the elements. He’d seen homeless people before, but the move from the country to the largely affluent Sydney hit like a shock to the nervous system. Here, their struggles were as tangible as the few possessions they squatted alongside.

The issue of homelessness is one that has been largely ignored for decades, at both a state- and federal-government level. Every night, roughly one in two-hundred Australians find themselves without a safe place to sleep and reports indicate that some 116,400 Australians are without a home – the highest number since the Census began estimating the prevalence of homelessness. In 2016, young people aged 15 to 24 made up 21 per cent of the homeless population, while women’s homelessness reached epidemic levels, with older women officially identified as the fastest-growing demographic at risk. And yet, these figures don’t even scratch the surface of the issue. Rough-sleeping might be the most visible symptom of a broken housing system, but beyond that lies the countless figures who are forced to sleep in their cars, live in motel rooms, or simply cycle through rooming houses.

Nedd watched as people filtered through the city streets, sidestepping the homeless like a traffic hazard to be avoided. He watched as those in need searched for a set of eyes to connect with, only for faces to turn downwards and away. As he tells it, “Initially I was taken aback at how I could help, and then I went, ‘fuck mate, they’re just people. Just talk. Just go up and start a conversation.’”

Every Tuesday, Nedd walked up and down the sidewalk, asking the homeless how he could help. Those who sat shivering and cold, he offered a hoodie. For others, he bought food and a hot cup of coffee. He tells me of one particular interaction with a guy named Dave, who Nedd approached only to be met with a reticent facade that refused to make eye contact. “He didn’t say anything. I was trying to talk to him and he just didn’t say anything. I asked, ‘Can I get you some food?’ And then he just started crying, and I’m like oh fuck. So I started crying and I just thought, there’s gotta be something else I can do because this just isn’t enough,” Nedd recalls. “Food doesn’t help. It helps for the next six hours, but it doesn’t help enough.”

The idea of lining up 50 marathons in 50 days to raise money for the homeless came to Nedd much like all his ideas do: while deep in the pain cave, body straining against the limitations of volume and load. After deciding one night to run 100 kilometres to Palm Beach and back, sustained only by a gatorade and three Cliff Bars, Nedd found himself lying in bed, gazing up at the ceiling in a world of self-inflicted pain. As he explains: “I couldn’t sleep because all my tendons were ruined and I was like, ‘this is terrible’. But then I was like, ‘I wonder what I can do next?I wonder what crazy thing?’”

Nedd set out for his first of the 50 marathons on August 31, 2020. There was no training block or time for tapering. Recovery was limited due to his work schedule, which saw him rise at 5:30 a.m to be on site by seven. He’d given himself a month from when he posted about the fundraising initiative on social media to the day that he set out on his first run. In that time, donations flooded in as curious individuals began to follow his journey with the enthusiasm of loyal fans to a live sporting final. Regardless of the weather or time of day, Nedd’s marathons became a daily ritual. In those instances where he could clock off work early, he’d go straight to Centennial Park or the treadmill. But where he finished work late in the evening, his would be a lonely figure out on the roads, identifiable only by a single low-beam of light dancing from a head-torch.

The first week was intolerable. Nedd awoke each morning to a body pleading with his mind to stop. Twelve days in, disaster struck. “I was probably eight kilometres into a run and my hamstring just tore. It deadset tore up into the back of my ass,” he says, the memory so visceral it contorts his features into a grimace while speaking. Anyone else would have made the decision to stop, to admit defeat in the face of their body’s limitations. But Nedd pushed on. With 34 kilometres to go, he got innovative: a half-stride on his right leg, and a full stride on his left. To this day, the twelfth marathon is the one that stands out the most for him. “I was yelling. I had AirPods in and I was just screaming and crying and going through every emotion you can imagine. I got on the ground just balling my eyes out and one of my mates picked me up, took me home in his car,” says Nedd. “I got in the ice bath and just thought, ‘tomorrow is a new day.’”

Nedd never set out to be lionised by the running community, but his 50 in 50 turned him into something of a celebrity. When the pandemic sunk its claws into every corner of the globe, blanketing the country in fear and uncertainty, a good news story was something to be coveted. In lockdown, empty months accumulated on the calendar with little to distinguish the passing of time. The world of professional sport had been put on pause and suddenly, the varied textures of human experience seemed perpetually out of grasp.

Amidst daily reports of rising case numbers and human lives reduced to a tally for the global death toll, Nedd’s daily marathons served as a reminder that nothing in life is guaranteed, but there is still joy to be found in the process if we are willing to look for it. He encouraged us all to find and embrace those rituals that serve no purpose other than contributing to the make-up of our identity: these are the rituals we wake up or come home to, for no reward or recognition. “We get so caught up in the whole ‘I can’t wait to achieve this goal, or achieve that’. I love every step of the run. Don’t get me wrong, throughout the 50 marathons, I got so excited for each day and finishing another one and ticking this off and what the next day would bring,” Nedd admits.

“For me to conceptualise what I was doing, I had to put it in basic terms: you’ve got to run a marathon. Just like brushing your teeth, it’s just another thing you have to tick off in your day.”

When Nedd completed his 50th marathon on October 19, people of all ages and abilities had come out to run alongside him, moved by the determination they had witnessed over the course of his 50 days. His mum and dad had made the drive from Forbes to Centennial Park and at each lap, he’d hear his dad yelling, “Come on mate! You’ve got this!” Few experiences might ever top the elation he felt upon finishing, looking behind to a crowd that wore the expressions of admiration and awe. Initially, he’d thought raising three-thousand dollars for the Red Cross to support Australians living in poverty would be a valuable donation. Upon completion, he’d raised $95,000.

And still, there was no ego. No sense of self-importance or desire to bask in the limelight. During a time of collective suffering, Nedd only wanted to show others what was possible. He wanted someone watching his journey to understand that his wasn’t a body primed for feats of endurance but a mind resolved to weather the storm. “When you’re day twelve and you’ve got a torn hamstring and 34km to go, no amount of publicity, no amount of followers, no amount of likes, no amount of people knowing who you are is going to get you to 42km,” Nedd says. “It’s what’s in your head, what’s in your heart. It’s what your desire is.”

4.

In the sport of distance running, pain is both endured and expected. It’s a voluntary suffering one signs up for and, remarkably, returns to time and time again. Where it used to be the case that the marathon was regarded as the ultimate torture chamber, in recent years feats of endurance have gravitated towards the brazen and extreme. A report published in May of 2021 illustrated the overwhelming popularity of ultra running, with a 345 per cent increase in global participation over the past 10 years. While 41 per cent of ultra runners now participate in multiple events per year, there’s been a levelling off of participation in the marathon and a decline in the five kilometre road race.

In conjunction with the ultra running boom, the fastest known time (FKT) attempt is also quickly becoming a popular pastime, with many forgoing races entirely in favour of such individual pursuits. To achieve it, a runner sets out to cover a given route or journey faster than the previous best known time. The allure here isn’t hard to see: where running was once celebrated for its accessibility, it’s come to be dominated by big data and the kind of technological advancements that shift the focus from one’s rigorous training regime and technique to the shoes worn on race day. The FKT then, seems to signal a return to that aspect of running that proved so intoxicating: the loneliness, the hardship, the individual pursuit made by a renegade and outcast – some of whom might be professional – but most of which are just your average person looking to defy the odds. Looking to test what it means to be human.

It’s this that Nedd has become intimately acquainted with. Ultra running presents a tempting elixir of struggle and euphoric triumph that is sure to convert most, inspiring in its participants a kind of reverence typically reserved for a cult. Questions arise out there on roads and trails that threaten to challenge your very existence and for many, the completion of an ultra marathon is conducive to a reassessment of one’s lifestyle and priorities. It’s understandable then, that on day twenty of his 50 marathons in 50 days, Nedd was already thinking of his next suffer-fest. This time he didn’t want to have to rely on the convenience of a treadmill, or a park situated nearby. He wanted to immerse himself in the danger ultra running presents, one that rubs right up against its power to change your life.

In December of 2021, Nedd found himself in conversation with a mate at the Coogee Pavilion. Perhaps he was simply engaging in lighthearted banter, or perhaps he understood that Nedd was searching for another test of his own potential – regardless, his mate spoke the idea of running 100 kilometres a day. “I was like, ‘Has anyone ever done that?’ And then I’m looking it up, and people had done 100km a day or more before, it just wasn’t across Australia,” says Nedd, a smile stretching wide across his face. “I said, ‘We’re on.’ And it’s been in the back of my mind ever since.”

Much of 2021 had seen Nedd sidelined due to injury. For six months, his routine was one of strength training and rehab, but even when he wasn’t out logging miles, his mind visualised it all the same. So that when he went public with his endeavour to run 3,931 kilometres from Cottesloe Beach in Perth, to Bondi Beach in Sydney, there was never a doubt in his mind that he won’t achieve the FKT by running 100 kilometres a day, every day, for 40 consecutive days.

Currently, Germany’s Achim Heukemes holds the FKT for the crossing of Australia, running from Fremantle to Sydney in 43 days. But Nedd, hoping to raise one million-dollars for the homeless charity, We Are Mobilise who do outreach programs on the street and provide those sleeping rough with food and hygiene packs, knows his is a cause that will power him through even the toughest of days. As he explains, “I feel there’s an untapped potential in a lot of us, especially myself. With the 50 in 50, someone had done it before so I was like, ‘well, I can fucking do it then.’ And that’s the thing, if someone has done something, that’s where I go, ‘I can do this.’ Why can’t I? I’m just another person. It sounds cliche, but there’s something deep in me that wants to find out what I’m actually physically capable of.”

5.

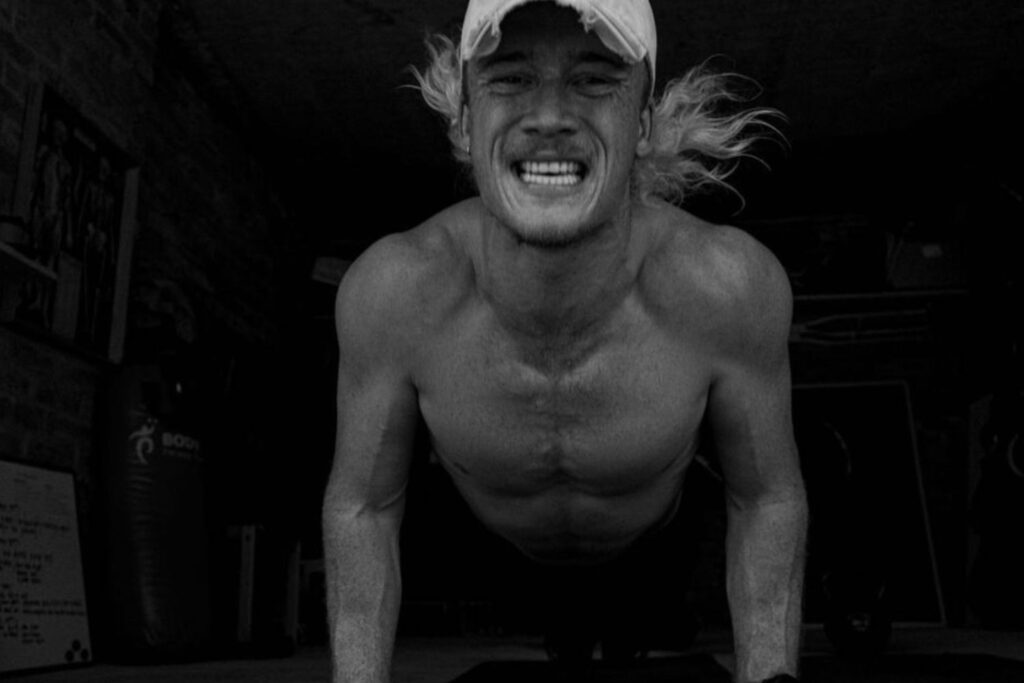

The bleached mullet is even more resplendent via Zoom call. No ring light required, this is the stuff of pure genetics and sodium hypochlorite. It still hangs heavy with the residue of sweat, which is understandable when Nedd alerts me that he’d been out on a run just minutes prior to our call, a notification on his phone alerting him to the need to hurry back to a computer screen. When we talk, he’s back living at the family farm, enjoying those long stretches of gravel road and flat tarmac he first discovered after turning his attention to running. He wears sneakers with a cushioned sole now, and has traded the rugby uniform for something more streamlined, made from materials coveted for their sweat-wicking capabilities. Now aged 23, Nedd’s maturity is foregrounded less in disposition and more in his approach to training; he appreciates the role of recovery, practices like meditation that calm the mind and ice baths to ground his breath. But still, there’s the palpable childlike enthusiasm that colours his expressions and extends beyond the screen, you place a certain faith in his every word like a quarterback receiving the coach’s play. September 1 is drawing ever nearer, but it’s clear Nedd doesn’t want to slow down the clock or make room for additional weeks of training. If he had it his way, he’d already be out there on the Nullarbor. “There’s times through this build up where I’m like, fuck. I just need to go now. Because I’m strong and I’m fit as well,” he tells me. “But you’ve got a higher goal, so I need to just rein it in. I’m going to nail the strength training, I know I’m fit enough. I just need to chill out until we get there.”

That’s exactly what brought him back to the farm. Granted leave from work so as to devote his focus entirely to the upcoming journey across Australia, Nedd’s daily routine is one of reading, sleeping and resting – that is, between the running and strength training. Of course, there are still logistics to work out and navigational routes to be mapped, all of which seems to be proving something of a nightmare for Nedd and the small team that will accompany him on his FKT attempt. As he explains, “I’m not running around Centennial Park, going to my bed, having a shower and having a sleep. There’s times where I won’t have food for five or seven days, so we have to pack and store and book in motels for showers and places to stay. And the days we don’t, we’re sleeping in camper vans.”

Raising one million dollars for homelessness is tough in any situation. The cause is a worthy one and Nedd’s effort to do so extraordinary. But still he finds that there are those who are somewhat reticent to reach deep in their pockets, yet all too willing to voice their doubts and project the limitations of their own minds onto the resolve of Nedd as he looks to push his body. Nedd only welcomes it. Back at his own place, he’d wake up to such criticism in the form of a ‘Fuck You’ wall plastered on the right side of his room. Alongside an A3 calendar of his training, he hung a sign with the words ‘Be Fucking Relentless: Let’s Go, You’ve Got This’ and directly below it read the comments from his adversaries. “All the people who have said, even the slightest thing that I can grab as a form as fuel, they’re in quotation marks – and then their name,” Nedd informs me. “I want the ‘No, you won’t do it.’ I love proving people wrong. It’s not the only reason, but it definitely adds. The homelessness, the desire to be my best self; it’s a very nasty concoction because I’ll get that shit done.”

Soon, Nedd will commence Hell Week, in which he’ll put his body through consecutive days of long mileage, runs on legs fatigued from heavy weights, and feeling the struggle of 100 kilometre efforts that drain the body and mind. The sheer volume is intimidating, but just talking about it, Nedd’s whole body jitters with excitement. He’s entering unknown territory, going to depths of the psyche previously unchartered, and that to him is cause for celebration. That even now, having amassed a resume of extraordinary feats of endurance, he is still a student to the art of this foot-sport we call running. “The mind drifts; the mind drifts everywhere and it questions why you’re doing these things. But it also goes, ‘god, this is good. How good is this?’ And I think you just have to ride the highs, ride the lows,” says Nedd. “There’s going to be days where I wake up and feel really, really good. And there’s going to be days where I wake up and feel terrible – and those are the days where you have to knuckle up and have a crack.”

That’s the thing about a guy like Nedd Brockmann: he likes to finish what he started, and to talk to him is to know with utmost certainty that this is a man who will achieve whatever he sets his mind to. I ask him about today’s run that our scheduled call so rudely interrupted. I wonder how it’s changed in recent years, if having some eleven-thousand followers on social media all intent on following your every step makes it difficult to safeguard and protect a ritual that is otherwise so sacred, such an integral part of your daily routine and identity at large. But with a shrug of the shoulders, Nedd can only offer the wisdom of someone who learned the value of simply doing the work, quietly and for yourself. As he tells me, “Today I took my watch off and just went, ‘just go for feel.’ And it’s so nice, because you can just enjoy the surroundings and go out and come back and do what you want. You’re just feeling it and actually enjoying the run.”

You get the sense that even without the fame or publicity, Nedd would be out there anyway, logging miles in the passing glare of headlights as the sun begins its commute skyward. What a lucky life it is then, that he’s sharing it with us all the same, that Nedd’s feats might inspire someone else to think that they, too, are just another person – one who might, if they work hard at it, be destined for greatness.

To follow Nedd on his Record Run across Australia and contribute to his goal of raising one-million dollars for homelessness, visit the official website. You can also keep up to date with Nedd’s journey via his social pages, here.

Nedd is sponsored by Puma and fuelled by ReMilk, a new milk to hit the Aussie market that’s nutritionally top-notch, with half the sugar and double the protein, while also being lactose-free.