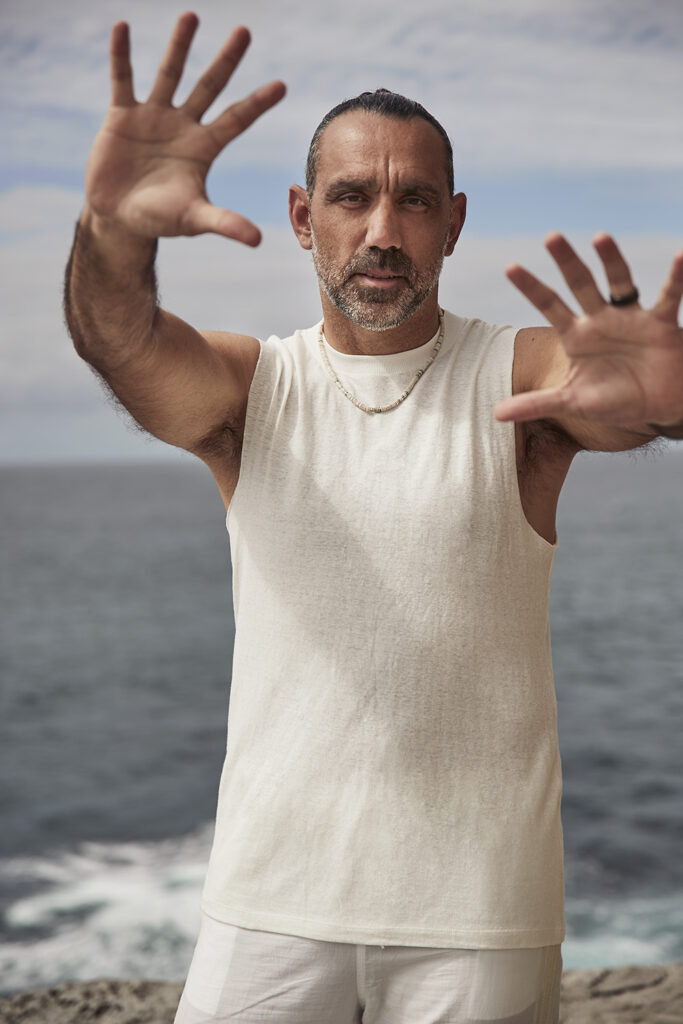

Adam Goodes is standing on the headland at Bondi gazing intently at a whale frolicking out at sea. “Look at him, look at him,” Goodes yells out to our crew. “Whoa, he breached there. That was like a side flick on your BMX. He got out of the water and then bang!”

The energetic mammal isn’t the only one in high spirits today. You’d have to say, after spending the morning with a carefree and at times jocular Goodes, that right now he’s pretty happy with the way his life is going, there’s not much about it that he’d change and, as he tells me, he’s comfortable in his own skin. So yes, I may as well say it: he, too, is having a whale of a time.

Which is not something you would have said about the 42-year-old, dual Brownlow medallist seven years ago when his AFL career came to an acrimonious and, in many people’s eyes, shameful end. The treatment Goodes received in his final years from sections of opposition fans left a stain on Australia’s most popular game that’s proven difficult to remove.

For his part, Goodes in retirement has chosen to look forward rather than back and put his energy into actions rather than words. He’s launched a raft of initiatives that aim to empower his people to seize opportunities in education and employment, including the GO (Goodes O’Loughlin) Foundation with Michael O’Loughlin and the Indigenous Defence and Infrastructure Consortium (IDIC). He’s also authored a children’s book series called Welcome To Our Country, which is giving Indigenous kids, including his own children – Adelaide, 3, and Otis, 1 – a chance to see their community represented in print. And he’s become an ambassador for wellness brand Wanderlust, a company whose values of inclusiveness, equality and connection align neatly with Goodes’ own post-footy focus.

But while he’s largely shunned the media spotlight post-football, Goodes remains a fierce advocate for his people, a position that still today in Australia requires strength and fortitude, even if it is, as Goodes sees it, largely a responsibility. “I think the strength comes from me going on a journey and learning about who I am as an Aboriginal person and understanding the history behind being an Aboriginal person in mainstream Australia,” he says. “And if I don’t have a voice as someone with the profile that I’ve had, then how is that going to make it easier for the next generation? I’m standing on the shoulders of my ancestors and the sacrifices they’ve made. So how am I making it easier for the next generation? I take that responsibility on quite honestly and proudly and I think a lot of other Indigenous role models do as well.”

A man driven by purpose and at peace with himself. The truth is you probably need both to be an effective leader. Less obviously, perhaps, it’s difficult to truly savour life’s sweeter moments, like watching a whale frolic on a sunny day, without them either.

Earmarked for success

You might be surprised to learn that, born in Wallaroo in South Australia, Goodes as a kid dreamed not of taking speccies in front of a packed house at the MCG but rather of hitting the back of the net at Old Trafford. His best mate, a kid called David Schneider at Forbes Primary School in Adelaide, came from a family of Brits who were rabid Red Devils fans. Goodes followed suit. “I was always thinking how amazing it would be to be playing in the English Premier League one day,” Goodes says, as we chat at a picnic table overlooking Bondi’s magnificent shoreline. “I also thought about how nice it would be to travel overseas and get paid to play sport.”

A rangy, athletic kid, Goodes took quickly to most sports but what distinguished him, even at a young age, he says, was his ability to listen. “I was a bit of a sponge and I think that was a big part of why I was able to be so successful in my life,” he says. “I was always open to feedback and criticism from other people.”

He got that, he says, from his mum, a member of the Stolen Generation, and from his respect for his elders more broadly. “Not having all the knowledge and knowing that my elders had more knowledge than me meant that actually I should shut up and listen and absorb this knowledge,” he says.

Adam Goodes would move to Horsham in Western Victoria to attend high school. By now he’d switched his focus to AFL. He would play for the North Ballarat Rebels in the TAC Cup as a 16-year-old, which led to him being drafted by the Sydney Swans as the 43rd pick in the 1997 draft.

“Sometimes you just need to be with yourself and your thoughts. That’s what meditation is and what it does for me“

Once he got to Moore Park, Goodes didn’t stop looking around for people to learn from, gravitating to his nephew Michael O’Loughlin and other Indigenous players on the team. “It was the first time that I’d been in an environment where I had multiple senior Indigenous men around me,” he says. “Mick, Troy Cook, Robbie AhMat. And I followed in their footsteps, the good and bad things that they did. It was a great learning curve for me.”

Adam Goodes and Michael O’Loughlin are literal blood brothers (and Bloods brothers) in what has become one of the defining friendships of Goodes’ life and, you suspect, a big reason why he’s in such a solid place these days. “There’s been a lot of ups and downs, more downs and I think that’s when you really see the strength of the friendships you have and realise how important they are.”

Indeed, where so many men lose track of mates once they enter relationships and turn their focus to their families, Goodes has worked hard to keep his ties strong. He still catches up with his old high-school mates from Horsham every year and more recently he and other Sydney-based Swans alumni have begun meeting up once a month for a beer. “That’s just filled another void,” he says. “We just book it in once a month, whoever can make it. It’s like a special men’s club. Dinner, beers. Perfect.”

On his terms

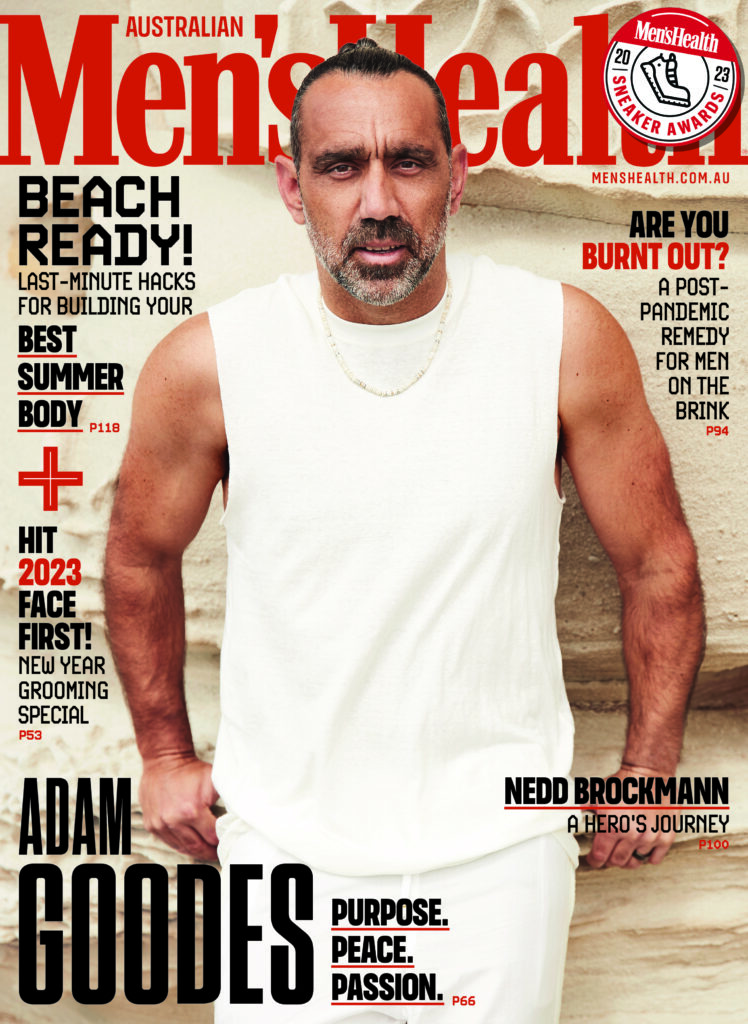

When Adam Goodes arrives at our shoot, he’s dressed in a plain white Tee, black shorts and black sneakers. The first thing you notice is his size. I’d forgotten he played some of his career in the ruck. He’s become a little more solid through the core and torso than he was during his playing days but there really is no mistaking a former athlete in the flesh. Even as the spotlight fades and they take on the familiar rhythms and tropes of civilian life, they’re always going to stand apart from the rest of us.

That distinction can mark them for trouble. What do you do when you don’t have the routine of week-day training, video sessions, the big game on Saturday? How do you stay in shape without someone giving you a program and grabbing at your skinfolds? How do you forge a purposeful life for yourself without the structure of a sporting club and the tug of ambition, particularly when, as you quickly and acutely become aware, no one is watching you anymore; nobody really cares?

Goodes loves it. Loves exercising on his own terms, maintaining a body that’s capable and useful, rather than one built purely for performance. “I feel healthier now than I did when I was playing because there was constantly something wrong with my body,” he says. “You’re pushing your body to its absolute limits every training session, every game. So, for me, all of the training, all of the meetings, that was wearing me down.”

These days Goodes runs as frequently and as far as he feels like, often pushing Otis in the pram on laps along the Bondi boulevard. “I don’t put too much pressure on myself from a fitness point of view,” he says, telling me he’s barely done any heavy lifting in the gym since he walked off the SCG for the last time. “I’m never going to get back to the peak fitness I had when I was a professional athlete. But I don’t need to. What I do need to do is to be fit and healthy for my kids to play with. That’s where my health will always be measured.”

What about the competitive itch? How does a former athlete scratch that? The answer is by taking park soccer “extremely seriously”. Goodes plays centre-forward for Waverley Old Boys Over 35s. Former Socceroo and SBS commentator Craig Foster is on the team, meaning Goodes doesn’t miss a chance to put his ears to good use. “He’s got incredible drills and a lot of enthusiasm for the game still,” Goodes says. “And like I said, I’m a sponge. I like to absorb that feedback and put it into practice.” The only thing missing, he says, is heavy contact. “I like to be physical,” he says. “I look for that. I like to be a presence up forward and I treat it just like any other game I play. Once I’m on a soccer field, I’m out there to win and I want to get better.”

Adam Goodes doesn’t meditate before contests as he used to before Swans games – he’s not playing for Brownlow votes. Instead, in retirement, he uses meditation as a way to decouple from the frustrations and aggravations of daily life. “I think I’m one of those people that when things aren’t going well and I’m frustrated, meditation grounds me,” he says. “Because life happens and unfortunately a lot of things attach to you. Usually jumping in the ocean washes those away for me but sometimes you just need to go to a quiet place and be with yourself and your thoughts. That’s what meditation is and that’s what it does for me. It’s an incredible tool.”

Much like his attitude to exercise, Goodes doesn’t put too much pressure or expectation on himself when it comes to practising mindfulness – that would be self-defeating – grabbing anything from five to 40 minutes when the opportunity arises. “That’s the way I think about all the things that I do,” he says. “I don’t beat myself up because there’s so much more to life now.”

Listen, learn, lead

As Adam Goodes and I are chatting, we’re occasionally interrupted by eager dogs escaping the clutches of their owners along this popular walking track. Each time Goodes stops to give the mutt a cuddle before an apologetic owner dashes over to retrieve it. “I love dogs. Love their energy,” he tells me, after helping a woman clip her pet’s collar. Later, a middle-aged man with a ponytail spots us, making a beeline for our table. He hands Goodes something I can’t see. Goodes glances at it. Later, he shows me what the man gave him. It’s a stamp with the Queen’s head on it. “I was wondering why he gave me this,” he says. Then he shows me what’s written underneath her majesty’s head: Terra Nullius.

You could argue this avid, socially conscious stamp collector could scarcely have picked a better person to bestow his unique gift. Goodes was named Australian of the Year back in 2014 in recognition of his leadership and dedication to the Indigenous community. But it’s what he’s doing post-career, which isn’t making the headlines or getting the recognition it deserves, that could be his ultimate legacy. That’s saying something for a bloke who made four All-Australian teams and was named on the Indigenous Team of the Century.

Go back seven years, in the immediate aftermath of his career, Goodes wasn’t sure what he was going to do with the rest of his life, but he was determined to let his hair down, at least for a little while. For six months he travelled the world with his now wife, Natalie, ultimately proposing to her on a trip that saw them take in Coachella, the NBA finals, the Superbowl and enjoy a European summer, among a host of bucket-list stops. Having worked to be debt-free by the end of his career, Goodes had plans to keep the good times rolling for two years. But just before he left, he was approached by a group with a proposal to start an Indigenous business enterprise. “They planted the seed and when I came back, I was like, Wow, this sits right in the sweet spot of what I want to do. This leads to work for my mob. It’s working with Indigenous entrepreneurs, working with government organisations, working with CEOs of big corporates. And I said, ‘Look, I’m in’.”

“I think what happened from the sporting field was I got the self-confidence to have a voice“

Adam Goodes started the business, IDIC, with Dug Russell, Michael McLeod and George Mifsud, becoming a majority owner and CEO. Throwing himself into the unfamiliar world of boardrooms, spreadsheets and PowerPoint presos, he once again drew on his ability to listen and learn. “I don’t have an MBA, I’ve never been to university, I’ve never run a business before but Dug, Michael and George had all been working in corporate Australia,” he says. “I just learnt so much off them.” From not really having a firm post-career plan, Goodes had managed to find a calling. “The opportunity was right there in front of me and now I’m still doing that seven years later.”

The other thing that’s happened post-football that will ultimately define him, as it does for any man who has kids,

is fatherhood. How, I venture, has it changed him? “I think I’d lived a very selfish life as a professional athlete,” he answers levelly. “And many of my ex-girlfriends could probably attest to that. It was probably the reason for a lot of the breakdowns in my relationships. But that selfishness was something I had to do for my sport and for my own personal performance.”

Once kids came along, Goodes says, the obliqueness and uncertainty of life gave way to clarity, purpose and responsibility. “Questions like ‘what’s life all about?’ actually mean something now,” he says. “You have a kid and you’re like, Okay, this is what it’s about.”

Like many new fathers, Goodes is determined to close the gaps he experienced in his own upbringing. “My father wasn’t around when I was a kid so the biggest thing for me is to be there for my children,” he says. “But also, I’ve got a huge responsibility to educate my children about who they are as Aboriginal people. I didn’t have that growing up.”

His children also inform his mission to make this country a more caring, compassionate and accepting place for everyone to live, something he knows requires him to stick his neck out now and then. That’s not easy but you’d have to say few are more practised at it than Goodes is. “We have to do things, we have to say things,” he says. “I think it’s not only a responsibility for myself, but for all of us and the communities that we live in to make it safer and better for the next generation.”

Ultimately, that will take leaders. And while AFL is no longer a big part of Adam Goodes’ life, he does credit its role in giving him the tools to drive change. “I think what happened from the sporting field was I got the self-confidence to have a voice,” he says. “I never wanted to be a leader until I started contributing in the Swans’ Bloods system and I thought, Wow, I could be a leader here if I exemplify these values and behaviours. I was able to captain the club for four years leading up to a premiership in 2012, which I’m really proud of. So, for me, I think understanding the power you have and the platform you have is really important. But more important is using that positively. It’s all about how can I use that to benefit our people?”

A Healthy Handpass

Adam Goodes recommends Wanderlust’s mushroom supplement to boost physical and mental wellbeing (Wanderlust Mushroom Multi, $35.99, wanderlust.com.au). If you’re looking to curb inflammation, Goodes suggests trying turmeric (Wanderlust Turmeric, $29.99 for 50ml). Always read the label and follow directions

for use.