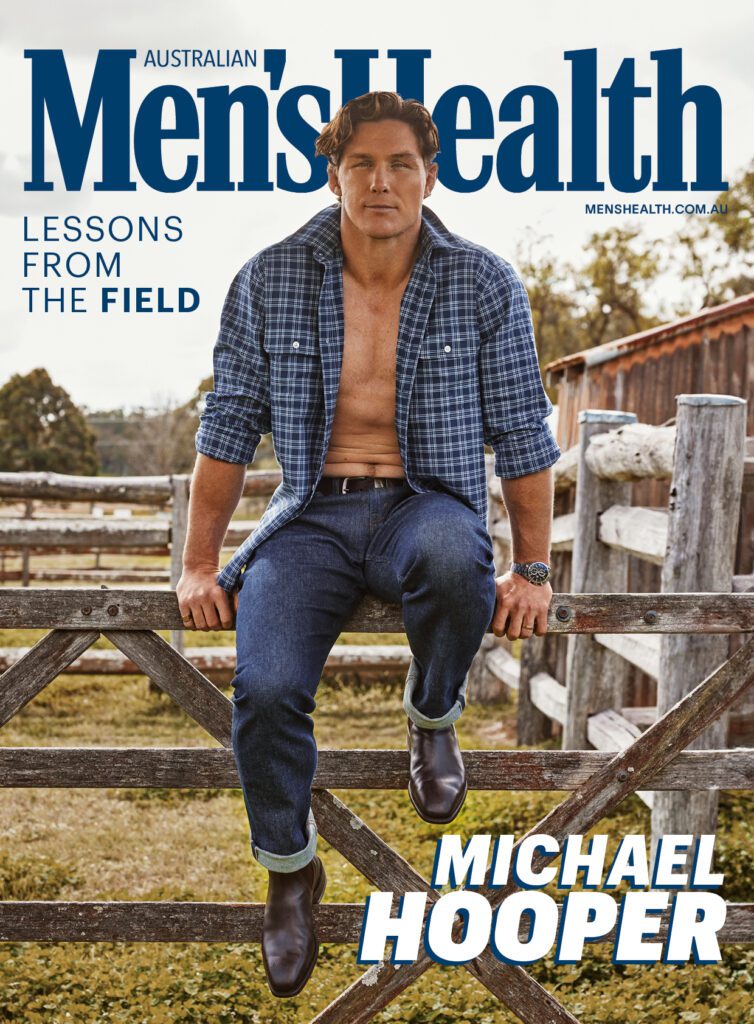

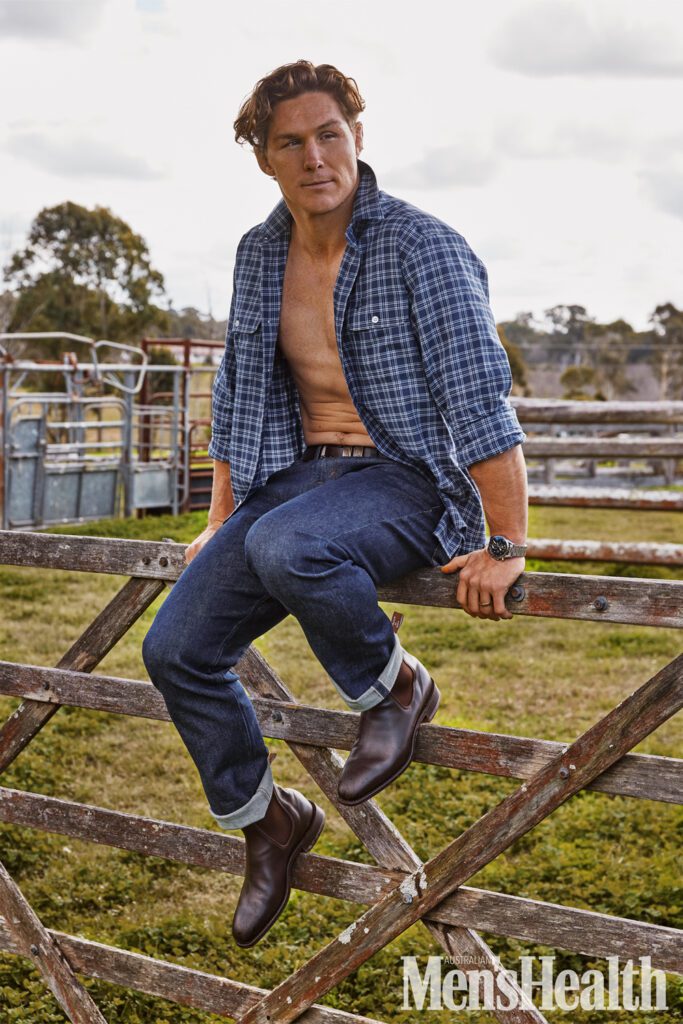

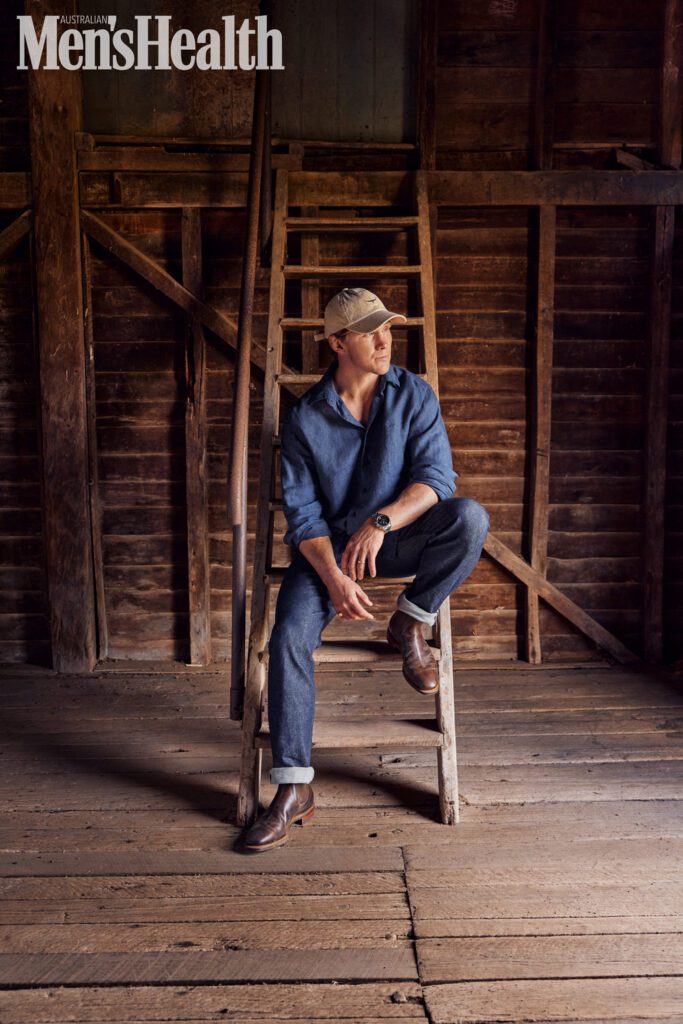

MICHAEL HOOPER’S RUGGED face is bathed in the morning light pouring through the window of an old timber shed at Belgenny Farm in Camden, an hour’s drive from Sydney’s CBD. The scars from a million mauls are hewn into his visage, his left eyebrow something of an old quarry of hits and bumps that our grooming artist is doing his best to disguise, though I think it lends Hooper a certain gravitas.

With his face on, Hooper steps over to a line of R.M.Williams boots that his one-and-a-half-year-old daughter, Adelaide, is curiously poking and prodding.

“Which ones should daddy wear?” Hooper asks her. “Do you think they’d fit you?”

Adelaide picks up one of the size 10s, but understandably isn’t overly concerned with what her dad wears, or what he does – or rather did – for a living. He’s just daddy. Not Michael Hooper, former captain of the Wallabies, four-time John Eales medallist, the fastest player to reach 100 test caps and one of the most effective openside flankers in the history of Australian rugby.

Chasing after or tackling – if you want to be cute about it – Adelaide and older brother Thomas, who’s two-and-a-half with a decent step on him, is Hooper’s main concern these days. The 32-year-old announced his retirement from Australian rugby – though, not the game altogether – back in June, after a failed attempt to make the Sevens team for the Paris Olympics.

You’d have to say retirement appears to be sitting rather well with Hooper, something he’s happy to confirm, though watching the Wallabies’ recent outings in the Rugby Championship, for which he did some commentary, did stir some wistful feelings in the moment. “We had some home test matches, and particularly the one against South Africa, in Brisbane, I missed it,” says Hooper, as we chat on an old picnic table on a grassy paddock that overlooks a vineyard. “The competitive juices get flowing. But then I got on a flight after the game, went home, woke up, and I was with my family the next day, and I wasn’t bruised, I wasn’t broken, and I didn’t have to think about, Was my performance up to standard, or What does next week look like? That was new for me and it was refreshing.”

Retirement isn’t something that snuck up on Hooper, as it does for many athletes. He knew he’d miss playing the game at the highest level. Why wouldn’t he?

“I miss when the lights come on,” he says, breaking into a deep-eyed grin. “I’ll always miss that. Speaking to some ex-Wallabies, they’re 45 and they still want to play. I don’t think that’s a bad thing. It’s not trying to live in the past. That’s part of you, and it’s part of me, but there comes a point where you think, Is the output to get there worth it anymore? You start to ask the question: Do I still have the same drive to be the best I can be?”

Good questions – the last is one we should probably all ask ourselves from time to time. For there will always be new fields, if not to conquer, to explore. And within them, new paths to tread.

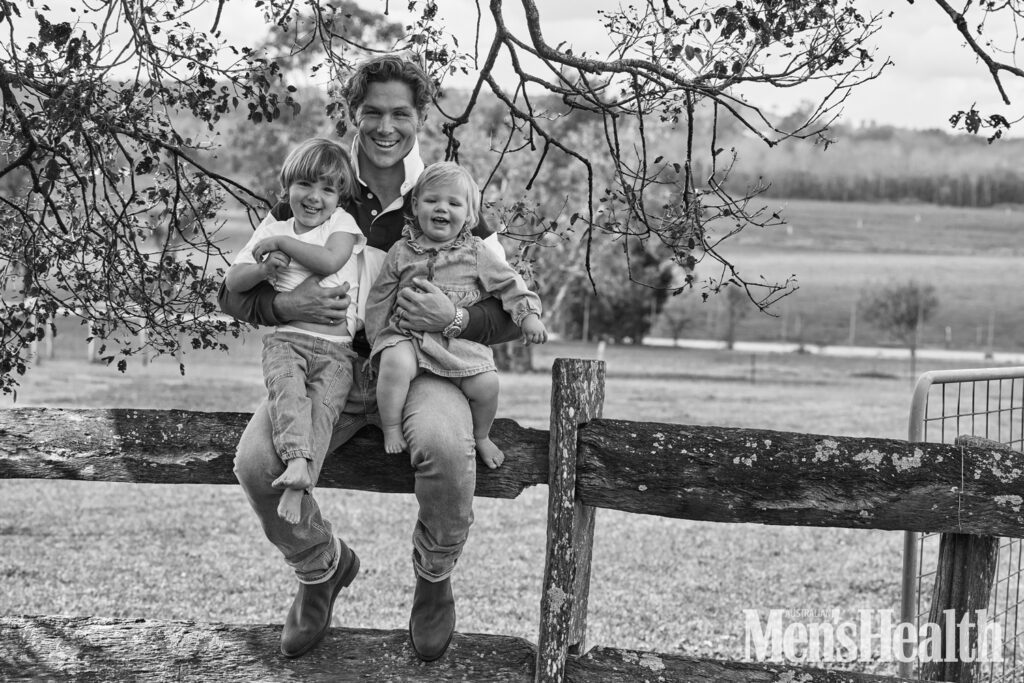

THOMAS AND ADELAIDE are wrestling on our photographer’s light shade, as we set up a shot in the farm’s front paddock. “She’s going to be a tough one,” Hooper says of Adelaide, who appears to be quickly getting used to the roughhousing that comes with having an older brother.

Maybe Hooper empathises with his daughter – just 18 months separates him from his older brother, the two enjoying a fierce rivalry during an idyllic childhood on Sydney’s Northern beaches. “We were competitive in everything we did,” says Hooper of he and his bro’s perpetual tussles. “If it was sport, if it was surfing, if it was PlayStation, we couldn’t play together. We couldn’t play against each other, because it would just end in an argument, so we’d always have to play on the same team.” He’s quick to add that the pair are close.

Hooper’s dad, an Englishman, had moved out here at 24. By some great miracle, he didn’t infect his boys with any sense of Pommy patriotism, as he introduced them to the oval-ball game.

“He very much supports Australia in everything,” says Hooper, who followed his brother into rugby at just five years old, playing first for the Manly Roos on the Northern Beaches and later for the Manly Marlins, as well as his school, St. Pius X College, in Chatswood.

At each level, Hooper’s goal was simple: be the best footy player he could be. Remarkably, he never looked much beyond that, even as he progressed through the representative ranks.

“I’ve seen photos of myself as a youngster with a Wallabies ball or saying, “Go Wallabies” in family home videos, but I don’t think it was ever really a thing that I thought about,” he says of one day pulling on the gold jersey. “It was always like, I love playing, I love competing. I was good at the game from an early age, so it was always wanting to prove myself at the level that I was in, and once I did that, getting to another level and doing it there again. And that’s all the way up to the Wallabies. People ask me, ‘When did you know you were going to be a Wallaby?’ It’s like, ‘Well, not until I played’, and then felt like I played well. Then, I felt like a Wallaby.”

Hooper would feel like a Wallaby for a long time. Indeed, such was his Atlas-like role in keeping Australian rugby afloat through one its most turbulent periods, he may never stop feeling like one.

HOOPER’S INTERNATIONAL DEBUT against Scotland in Newcastle in 2012, would prove to be suitably cataclysmic, the rugby Gods perhaps heralding the beginning of a special career by unleashing a once-in-10-year storm.

“It was the first Test of the year and this storm front was coming from down south and was going to hit right at kick-off and sure enough it did,” recalls Hooper, who prior to his national call-up had made his Super Rugby debut for the ACT Brumbies in 2010. “I was a reserve in that game, and I just remember sitting on the sideline, freezing, the wind and rain lashing over McDonald Jones Stadium, and just thinking, Oh, God. But you get your cap and you just try and seek more after that.”

Right from the start, Hooper would face ferocious competition for his position. David Pocock also played openside flanker and was regarded as perhaps the best player in the world at the time. He provided a benchmark Hooper strived to reach for himself. “Dave Pocock’s a legend, great player,” he says. “That position has always been heavily battled. It makes you a little bit self-conscious, but it’s good because you have to keep staying on your game.”

Hooper would become the second-youngest player to log 50 Test caps and fastest to 100 caps, an incredible feat in a game in which men weighing upwards of 120 kg crash into each other for two hours. There’s no doubt you need a certain amount of luck to stay on the paddock, something Hooper acknowledges.

“There’s an element of luck in any sportsman’s career,” he admits. “The thing that coincides with luck is being ready to take your opportunity when it comes, and fortunately for me, I don’t think I would have [played as much], had Dave Pocock not got injured. He was at the top of his game, and he gets injured and that opens the door for me. At that point in time, I was confident, I was fit, I was all these things. So, when that position opened, I was ready to go.”

Hooper attributes his incredible durability to “doing the little stuff”, as well as pointing to something a little more surprising: going all out, all the time. “I think going all-out with that intense effort helped me,” he says. “I found that sometimes when you’re at training and you’re not quite switched on, you get bumped and you get caught. I found going hard was actually a bit of an injury prevention [tactic], weirdly enough, and probably coinciding with that, I trained with a similar intent to how I wanted to play.”

He learned that, he says, from those who came before him, singling out Adam Ashley-Cooper as a mentor. “I saw that the guys that trained really hard, that made them durable for the game and because they were doing it a lot, their body was hardened and battle ready.”

Hooper’s availability, along with the standard of his play, was perhaps a factor in him being given the Wallabies captaincy at just 22. It was too young, Hooper says now, though to be fair, it’s a job in which you never stop learning.

“I had no idea what I was doing,” he says. “You’re still trying to work yourself out. Your mates are out doing whatever they’re doing, and you’re trying to lead a team, and I probably wasn’t equipped for how to do that as well as I could. But right until even the last couple of years, I’d still say I had plenty to learn. I think that was the realisation. When you realise how little you know, it’s probably like, Oh, God, whereas when you’re young and dumb, you’re like, We’ll be right, and then you kind of go, Oh, are we? and you’ve got to go to the well and start learning.”

What he lacked, Hooper says, was a recognition and appreciation of the dimensions and layers required to lead a team comprised of men at different stages in their lives and playing careers. In the absence of that understanding, he largely sought to set the standard and hope the team followed.

“I was much more of a by-actions person,” he admits. “You turn up, train hard, do whatever you need to do, then do it again the next day. But I didn’t understand that there’s different levels to how people need to get there. What’s different for a dad, with a heap of other things going on in his life to turn up and empty the tank and train, is very different to what it takes for a 22-year-old. I didn’t understand, and that’s why I say I wasn’t equipped. I didn’t have the empathy to see the different needs and dynamics of the team.”

His advice for anyone taking on a leadership position, particularly a younger person, is straight forward: ask for help, something Hooper himself worried would count against him in the early days of his captaincy. “I was offered help early on in my career and you kind of don’t want to look like you don’t know what’s going on, so you don’t utilise that as a resource,” he says. “You don’t have to be a silo. You’ve got to make a stand on some things, but you can certainly vet your opinions and your decisions by just asking for help from somebody who’s done it before.”

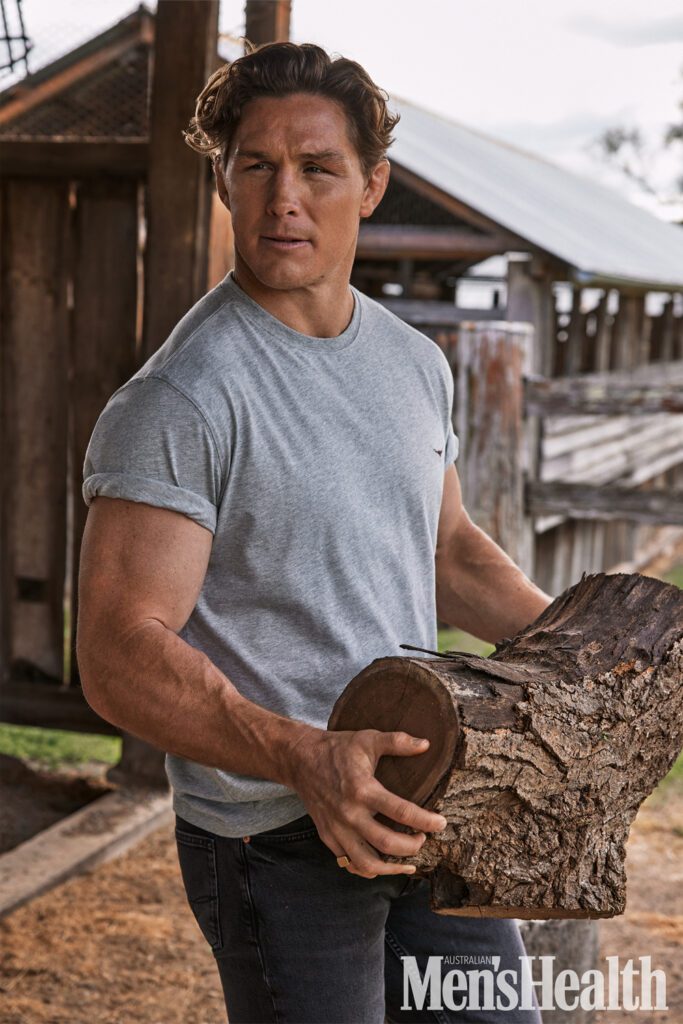

HOOPER’S BICEPS ARE rippling out of the sleeves of his T-shirt, as he hauls a log around in front of the farm’s old shearing quarters. He hasn’t lost too much in terms of size and definition in the month or two he’s been out of the game.

But while Hooper’s physical style of play was a hallmark of his career, he admits the mental demands of the game and the responsibilities he shouldered as captain gradually wore him down. In 2022, Hooper sensationally left the Rugby Championship in Argentina, 24 hours out from kick-off. The question everyone asked at the time: why?

“I was going through some changes in my life,” he says. “We had recently found out we we were pregnant again. I was away from home. Leaving home was hard. It grew even harder with having kids at home and wanting to be around. I was more uptight, more anxious than I’d been. There were a few more things that I didn’t quite understand going on for me, and my head wasn’t focused. What’s anxiety? Anxiety is worrying about what’s in the future. I was worried about my health, how my family’s coping at home, what the next couple of years look like. All that stuff.”

Very normal stuff, I point out. “Very normal stuff,” he agrees. “But I didn’t know that and it just became a loop. I was wound up tight because of those things and the environment. You’re like, I’ve got to put this away, but your body’s telling you, Hey, you’ve got to deal with this stuff.”

Years of pushing his body to the limit were also catching up with him, he says. “I’d been treating my body a certain way and working at that upper end of burning the candle,” he says. “My issue was I wasn’t replenishing myself in other ways or understanding these new feelings that had come into my life. I was like, Okay, well, I’m not wanting to play. I wasn’t in the right position to play and play well and lead a team. I needed to go away and see if that was something I wanted to get back.”

Quitting the tour was both a hard decision and an easy one, he adds. “It was a hard decision because I love representing my country and the team, but it wasn’t, because I wasn’t going to give my best performance and I’ve always been a believer that you’ve got to be 100 per cent into it.”

Upon his return to the team, in October 2022, Hooper was very clear that he wasn’t “cured”, an acknowledgement that mental health, for all of us, is something that fluctuates.

“I see it like an injury now,” he says. “If I’d rolled my ankle that week at training and gone home for a month, I don’t think it would’ve been a big moment but because it’s mental health, it seems to be a big deal. But I don’t see them as any different. Physio is the same as going and speaking to someone. It’s just harder to quantify.”

Hooper’s face may carry the physical scars of a career marked by visceral levels of physicality. But the bumps and bruises you can’t see, those we all bear at different times in our lives, they need tending too.

HOOPER IS WALKING up Belgenny Farm’s dirt driveway dressed in a trench coat and holding a bag, as if he’s returning from a day’s work in the city. His wife, Kate, is approaching from the opposite direction with Thomas and Adelaide, who upon seeing their father, run down the driveway to greet him. Our stylist had planned a different set-up to shoot the kids, but as Hooper scoops the pair up, the moment is too cute to resist. The photographer duly clicks away.

I ask Hooper how disappointed he was to miss out on competing for Australia as part of the Rugby 7s squad in Paris. “It was going to be a cherry on top,” he says. “So, it was cool because I’d never thought about going to the Olympics. I thought I’ll try and rebuild my body.” He’d had some calf issues in 2023 and had more while training for the Sevens. After he was cut from the squad, Hooper announced his retirement from Australian rugby, but not the game altogether. He’s keen to play in Japan, sooner rather than later.

“I’ve had a good break now, so I’d be open to going next year. But getting to the right club, right place, is going to be tricky.”

While he waits to see how that pans out, I wonder how not playing is sitting with him. How does this period of shadow retirement compare to the notions he had in his head of what his post-international career might look?

“Your mind sort of tells you different narratives, mine certainly did. Retirement’s never going to come. Then, you get in hard times in your career, and you’re like, Oh, I just want nothing more than to not have these problems and these issues, and you forget about some of the great stuff that rugby gives you. Then, there’s that excitement of doing something else. What else could I do? It [rugby] is only one part of life. There’s so much out there that’s exciting.”

He knows he wants to stay connected to the game he loves and has done so much to keep alive in this country. He’d like to help the next generation realise their dreams and to further develop the leadership skills the game has given him. “I love that about rugby,” he says. “I love that I had to try and learn and become better and I still think there’s plenty to learn in that environment.”

Yes, he’ll miss the moment the lights come on, but he’s thought carefully as to how to deal with their absence. “I put a bit of time into understanding what the things are that you miss,” he says, before telling me there’s four “buckets” that rugby ticks off that he’s looking to fill in new ways. “It has your schedule lined up for you, but it has your mates – you’ve got no need to text anyone. There’s training, so that’s your social element. There’s a physical element, you’re getting fit. Then, there’s what I call the spiritual, or the drive to be your best, to try and win a World Cup or something else. That gives you motivation or passion. You want to keep learning and growing and striving to get better at something.”

As the shoot wraps and I watch Hooper head back up the dirt road with his family, I’m conscious that we’ve caught him today between life stages. You get the feeling he’ll never stop seeking to learn and to grow. Those too, are things you can’t quantify, but perhaps you can see, or get a sense, of something else there in Hooper’s battle-hardened face: wisdom.

Michael Hooper is an R.M.Williams friend of brand.

Michael Hooper’s training regimen

Hooper is keeping himself close to playing shape by training 5-6 days a week in short sharp sessions of Maximal Aerobic Speed (MAS) running. What’s MAS? Put simply, it’s the lowest running speed at which VO2 max occurs and is typically referred to as the ‘velocity at VO2 max’. Hooper’s goal is to be fit enough to take on a challenge, like a triathlon, without too much notice. “I want to be fit and healthy, so that if someone said to me, ‘Let’s do a triathlon’, not an Ironman, but like a Noosa triathlon, I’d be ready,” he says.

Here’s a breakdown of Hooper’s training sessions:

MAS running

- Run 54m, rest 10 secs x 12

- Repeat 4 times, resting 2 mins between rounds

Conditioning circuit

- 500-metre row

- 25 burpees

- Barbell high pull at 40 kg x 10-15 reps

- X 4

Weights

- Bench press x 5 at 100kg or 2-3 x 120kg

- Chin-ups to failure

- Shoulder raises x 10 on each side

- Single-leg box squat x 10 each side