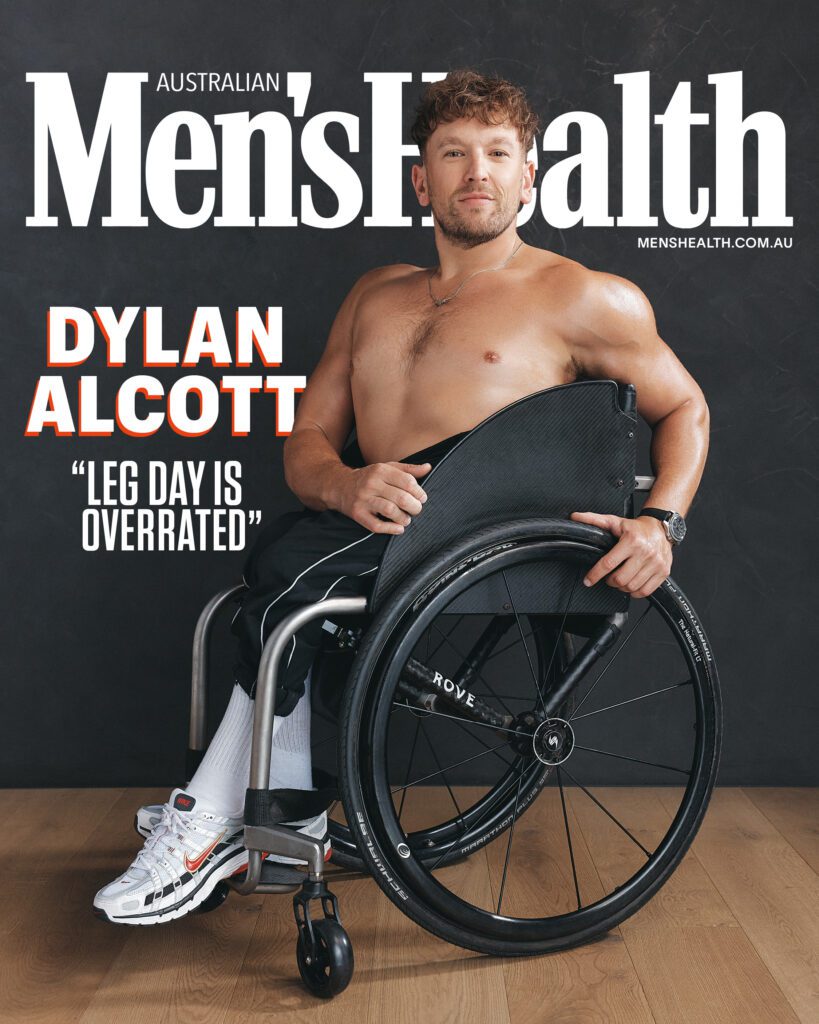

DYLAN ALCOTT, you could say, has an aura. Irrepressible, charismatic, with a healthy sliver of Aussie larrikin spirit, as he wheels his way into Men’s Health’s shoot at One Playground in Sydney’s Marrickville, he informs our stylist that he’s going shirt-off on the cover today. “I didn’t work this hard to hide anything,” says the 33-year-old, 23-time Grand Slam winner, four-time Paralympic gold medallist and 2022 Australian of the Year.

Soon he’s on the floor with his trainer, Jono Castano, who’s holding his legs, as Alcott knocks out some pre-shoot push-ups, before he grabs some dumbbells and launches into a series of biceps curls and shoulder presses. Once we start shooting, Alcott offers suggestions to the photographer on composition and camera angles, making it clear how important it is that his wheelchair is highlighted front and centre.

Alcott has trained for 12 weeks for this moment, but the truth is, today is not the realisation of a lifelong dream – as Alcott explains, when he was a kid, the idea of someone with a disability being on the cover of Men’s Health wasn’t something to which he believed he could even aspire. Instead, it’s the latest achievement in a life dedicated to pushing through perceived obstacles and challenging perceptions of what a person living with disability can do.

“I used to read Men’s Health when I was a kid,” Alcott tells me after the shoot wraps. “I never saw anybody like me doing anything like this. Anyone with a disability at all really. And that would’ve been pretty life-changing for me when I was really struggling with my own self-worth, my body image, getting bullied about my disability. It would’ve been incredible. I don’t have abs, I’m a paraplegic – it’s really hard to get abs. I didn’t used to love my body. I still have moments where I don’t, but I was like, ‘You know what? Lets go kit off on the cover’. It really pushed me.”

By taking on this challenge and putting his body on display in perhaps the most public way possible, Alcott confronted, head on, long-held insecurities about his physique and his self-image. “I learned that I can really do it and be proud of how I look and not be embarrassed about my body, my stomach,” he says. “It’s important to really have that self-worth and love yourself before anyone else can love you.”

But as well as seeking to inspire, Alcott also sought to educate. “I want to remind personal trainers, people that own gyms, that you need to be accessibly inclusive for our community,” says Alcott, who among his many projects since retiring from tennis, is an ambassador for KIA Australia and Longines and has founded the Dylan Alcott Foundation, helping young Australians living with disability overcome the barriers of entry to sport. “I wanted to train, to show them [trainers] that we can do it. But also, to show people with disability who might’ve had an accident or have never done this, that you don’t have to train like an able-bodied person, you just have to train in your own way. You have to figure out what works for you.”

Here, in his own words, Alcott breaks down his 12-week challenge, something we at Men’s Health usually call a ‘transformation’. In this case, that might not suffice. Alcott’s journey is bigger than that; more far-reaching and likely more impactful, a potential pillar in a long overdue reckoning in how those with a disability in our community are perceived. Dare to dream, goes the saying. Alcott’s message: dare to do it.

I’VE ALWAYS LOVED sport, but I couldn’t really access it as a kid. I played with my brother in the backyard, but I was always the timekeeper or the manager. I got bullied a lot and hated my disability. I was embarrassed about it. When I looked at Men’s Health, I never saw anybody like me, not even close. And that’s hard, to be honest. If I could go back and tell that little kid that you’re about to be nude on the cover of Men’s Health, that kid would not have believed it.

I do like to think he was a good kid, but the truth is, he wasn’t a happy kid and he wasn’t a confident kid and he wasn’t going to the gym. He was eating pizza on the couch and playing video games.

What really saved my life was finding Paralympic sport. Not just the physical benefits and the mental health benefits I got from it, but finding my community, my tribe, other people with disability who were happy, who were thriving – not just surviving – who were having a crack. I’m very lucky for that, I really am.

I wanted to pursue sports just because I wanted to be like my brother and like everybody else. We live in a sporting culture. And I’d be lying to say that as soon as I started, I had a lot of people telling me that I was good. I was like, Wow, I love this. Did I think I was going to win gold medals and Grand Slams? Absolutely not. I just loved pouring my effort and competitive nature into something. I couldn’t get enough of it.

The reason I loved it was because it made me feel free. Free of my own lack of self-worth, free of getting bullied. I was out there having a crack. It was just amazing. When I was 14, I started playing wheelchair basketball. When I was almost 16, I was like, Oh my god, I could go to the Paralympics when I’m 17 for either basketball or tennis. I had to pick one. I picked basketball, we won the gold medal, great choice. And then I was off to the races from there.

I AM COMPETITIVE but not against my opponents. I know that sounds weird. A lot of athletes get drive from, I want to beat that guy or I want to beat that team. I never hated anyone that I played against. I didn’t even think about them that much. I wanted to prove to myself that I could do it. That’s how my mentality worked. But I also wanted to prove to society that you should watch Paralympic sport because it’s entertaining, because it’s elite, that was my driver. My purpose was changing perceptions around disability. I put a lot of pressure on myself to prove that.

Later in my career I didn’t do that because I put too much pressure on myself. I realised I didn’t have to prove anything to anyone. I just had to go out there and enjoy myself and try my best. And that was why I ended up winning everything, rather than trying to prove something to Australia or the world.

I’m competitive with myself to want to do my best but when I lost big tournaments, I never got angry. I was just sad that I’d missed an opportunity for myself. When someone else beat me, I was pumped for them. I lost my last match. I don’t even think about it. I could not give a shit now. People say, “How many Opens have you won?” And I go, “I forget”, because I don’t count them. It’s more about the mission and what it meant for me.

WHEN I STARTED this challenge, I was far from my athletic peak. When I won Australian of the Year, I spent 245 days on airplanes that year, with 370-odd engagements and I didn’t give a shit. I was just like, You’re retired. So, I blew out. I probably put on 15 kilos, but I didn’t mind too much. But I realised that by not being active, it was really affecting my mental health, because as an athlete you get the benefits of being active for your mental health, for free. So, I was like, Why am I so grumpy and tired? It was because I wasn’t being active. And I also saw myself on TV and I had about four chins and I went, Alright, let’s change that.

I think what was in my favour with this challenge was that Jono, my trainer, and I live in different states. It was quite funny; I was sending him nude photos – well, I had my underwear on – every couple of days to show my progress. And my girlfriend’s like, “Who are you sending sexy photos to?” I said, “That’s just Jono”.

But what really worked in my favour was having the ability to smash myself in the gym without somebody there pushing me. That’s a really hard skill, if you’re not an athlete. So, with the sessions with Jono it was easy because he’s like, “Now, do it”. When I’m in Melbourne in a cold gym in my garage going, I don’t want to do this, I had that internal drive to do it because of my athletic background, but also because I wanted to show the world that people with disability can be sexy and ripped on the cover of Men’s Health. I had that purpose behind me, not just ‘I want to look good’. That wasn’t my purpose in this. My purpose was bigger than that.

When people train me, because I’m disabled, sometimes they’re scared of breaking me or hurting me. So, I stupidly said to Jono, “Man, I know I’m in a wheelchair, don’t go soft on me, you can smash me”. That was the dumbest decision that I ever made because from day one he smashed me and I was like, Am I going to be able to do this for 12 weeks? But I loved it. It was so awesome. He really took into account changing some exercises to be accessible for me, being inclusive in the gym but not shying away from some things. He was like, “Can you do this? Let’s figure out a way to do this”. Not, “I assume you can’t do that”.

It’s hard when you’re a paraplegic, you can’t really get abs. I used to worry about my weight. Fuck weight. It’s about how you feel. I know it [weight] is kind of a good benchmark, but really, it’s about how you feel. So, what I was really worried about was feeling good and looking good. Those were my benchmarks.

Day one, in the gym I had to get 30 cal on the Ski-Erg. It took me three-and-a-half minutes. By the end of it, yesterday, I did 40 cal on the SkiErg in 2.50. I’m also back to my athletic best in chin-ups, all that kind of stuff. I would say I am close to as fit as I was at my peak as an athlete. I think my fighting weight when I was playing tennis was about 65 kilos. When we started this, I was about 70 kilos and today I’m a bit under 62.9 kg. I lost about 10 per cent of my body weight.

THE HARDEST PART of this challenge was the travel. Across the 12 weeks, I had a trip to America, I had 10 days in Southern Africa and a week in the south of France, all for work. Safe to say there weren’t as many gyms where we were in South Africa. I was doing push-ups in car parks, doing hill sprints, just trying to find a way to train. And I think the biggest thing that I learned, and I love educating people about, is that when I retired from sport, if I didn’t have an hour-and-a-half to train, I didn’t bother because as an athlete, that’s how long you need.

When you’re not a professional athlete, you’ve just got to do something, just for your mental health as much as anything, and then the physical health benefits will come.

You just need 45 minutes to get out there and have a crack. Do some hill sprints. If you’ve got a gym, do a session, whatever it is. I had a day where I started in Brisbane, flew to Melbourne and ended up in Perth. I was wrecked, right? But you get to the hotel, you do half an hour or something in the gym. Afterwards, I just felt better.

When I landed in France, the first thing I did was a session. Why? Because I felt better. It helped with my jet lag. I told myself I was doing it for Men’s Health, but really, I was doing it for me so that I felt good. It’s so easy to eat room service, not go to the gym, have a nap, and you’ve just got to make sure you get out there and do something. It really does help.

I WANTED TO take on this challenge, not only to normalise disability but to change perceptions. I would tell people I’m doing the cover of Men’s Health. They’d be like, “What do you do in the gym?” Genuinely. It’s like, “Great question. Let me show you”. Imagine if we inspire a young trainer to want to know more or a young person with a disability to get out there and have a crack. That’s what it’s about.

I often get called an advocate and role model and that’s lovely. But I don’t wake up going, How am I going to advocate today? Or What angle am I going to push? I just get up and be myself and that’s hard enough as a person in the public eye. I’m authentic and vulnerable when I feel I need to be or want to be, but I also look after myself on that as well. I really don’t try too hard and think too much about how I want to sculpt my brand. I’m just being myself.

When I was 12, I met Adam Gilchrist. I love Gilly. He came up and he goes, “Hi, I’m Adam”. And I went, Fucking, of course you are”. Why is he saying his name’s Adam to me? And I was like, Oh, because he’s just Adam, he’s a person. When people come up to me, they go, “Oh, my God”. I say, “Hi, I’m Dylan”. They go, “I know”. I go, “Yeah, but what’s your name?” I think it disarms people and that’s what I want because I’m equal to them no matter what we both do.

My number one priority in life is just being a good person who enjoys my life. I’m a smart ass, self-deprecating, a dickhead really, in a good way, like anybody else. And I think that’s really important. A lot of people, when they get in the public eye, they portray something they think society wants. That’s really tiring and hard work and I couldn’t do that. But also, when I started in the media, I was a bit self-conscious about my disability. I was trying not to talk about it, not show it. It’s like, No, no, it’s a part of who I am. So, I waved all that away and guess what happened? Everything started becoming real, and I was like, Oh, they actually don’t care that you’re in a wheelchair. They care about your personality, if you’re a good person, if you can take a joke.

You see me on TV, I’ll make a joke about my wheelchair. You’re allowed to laugh. I think that humour is a really good way to normalise disability, so I’m always going to be myself. Life’s about living and I just get out there and have a crack.

MY ADVICE TO anybody who wants to change something in their life, is four-fold. Firstly, there’s power in authenticity. Saying you want to change something because you genuinely do, is so important.

Secondly, the power of vulnerability. If you want to change something, the best way to do it is to ask for help. Don’t try and do it yourself. I learned that young, when I was really struggling with my mental health. I didn’t tell anybody because I felt like a burden, an embarrassment. It was silly. It’s okay to ask for help.

The third one, which sucks; you’ve got to work hard to change things. You’ve really got to put the time and effort in.

But the most important thing, have a crack. Just start. We always talk ourselves out of everything. Just go, I want to do that. You’ll be horrible at it when you first start, and that’s okay. It’s okay to be bad at things. You get better over time.

Dylan’s 12-week training regimen

Alcott worked out with trainer Jono Castano, founder of Acero Gym, who gave him a classic push/pull split routine with a cardio session. Use this routine to build a shredded upper body, because as Alcott says, “Leg day is overrated”.

PUSH SESSION

- Ski-Erg x 30,25,20,15,10,5 calories

- Shoulder press x 20

- Push-ups x 20

- Triceps push-downs X 20

PULL SESSION

- Ski-Erg x 5,10,15,20,25,30 calories

- Chin-ups x 12

- Curls x 12

- Lat pulldown x 12

CARDIO BOXING SESSION

- Bag work x 1min

- Throws to sky x 1min

- Battle ropes x 8 rounds

PAD WORK x 6mins

- Jabs x 20 secs

- Hooks x 20 secs

- Uppercuts x 20 secs No rest

PUSH AND PULL SESSION

- 1A Ski-Erg x 1 min

- 1B DB lateral raise x 12

- 1C Face pulls x 12

- 1D DB hammer curls x 12 X 5 sets

- 2A Ski-Erg x 30secs

- 2B Arnie Press x 12

- 2C DB Frontal Raise X 12

- 2D Pronated cable rows x 12 X 5 sets

Dylan’s nutrition plan

Alcott’s diet plan was a simple high-protein, complex-carb regimen that allowed him to build muscle while shredding fat:

- Prepackaged high-protein meals x 2 per day

- Protein shakes x 2 per day.